Habeas Corpus: A Tug-of-War Between Power and Liberty

Habeas corpus has received renewed legal interest amid recent courtroom clashes over the Trump administration’s immigration policy. As political factions wrestle over its definition and limitations, many Americans are left wondering: is it a spell from Harry Potter… or something judges actually say in real life?

Habeas corpus is Latin for “you have the body.” It’s a legal action, or writ, that requires a person under arrest to be brought before a judge or into court, ensuring protection against unlawful detention.

Yet when questioned during a Senate hearing on May 20, 2025, Homeland Security Secretary Kristi Noem interpreted habeas corpus as “the president’s right to deport people.” Her answer triggered immediate public uproar.

Was she outrageously wrong, as many have claimed? Not entirely—at least not when viewed through the long lens of history…

The Evolution of Habeas Corpus

In medieval England, all legal authority technically flowed from the monarch. The writ of habeas corpus began under King Henry II as a royal command; the King’s judges used it to order a jailer to bring a prisoner to court so that the lawfulness of the detention could be reviewed. Just as the Supreme Court noted in cases such as Boumediene v. Bush in 2008, this writ originally served “to enforce the King’s prerogative to inquire into the authority of a jailer to hold a prisoner.” In other words: “Hey, who gave you the right to lock someone up? We’re the King’s court; explain yourself.”

In its early form, habeas corpus was a way for central royal authority to keep local lords and officials in check. It was not meant to be a tool to check state power, particularly executive overreach, until the late 17th century. With the passing of the Habeas Corpus Act in 1679, the writ was formally codified as the right to challenge detention, preventing indefinite imprisonment by the Crown. It made it harder for monarchs to detain people without trial.

How did habeas corpus go from being a leash in the crown’s hands to a collar around its neck? The answer dates back to the turbulent era in England leading up to the historic signing of the Magna Carta in 1215.

In 1199, King John inherited a kingdom in political, financial, and moral disrepair, and his own disastrous leadership only made it worse. By 1204, he had lost most of his territory in France, notably Normandy. To fund military campaigns and reclaim lost lands, John imposed punishing taxes, fines, and scutage (payments in lieu of military service) on his barons. He frequently manipulated the legal system to punish enemies, enrich himself, or silence critics.

Fed up with John’s abuses, a coalition of barons rose in open rebellion. They captured London in May 1215 and forced King John to the negotiating table. The result was the Magna Carta, a treaty between King John and the lords, signed at Runnymede on June 15, 1215.

While the term “habeas corpus” does not appear explicitly in the original Magna Carta, its spirit is strongly embedded, particularly in Clause 39, which states:

“No free man shall be seized or imprisoned, or stripped of his rights or possessions… except by the lawful judgment of his equals or by the law of the land.”

Clause 39 was the barons’ response to King John’s authoritarian abuses of justice. It was meant to protect the nobility from illegal imprisonment and arbitrary punishment.

Over the next few centuries, English common law built upon this principle. By the 14th century, courts began issuing writs of habeas corpus, but enforcement was neither consistent nor reliable. The monarch and his allies often ignored or bypassed it, especially during times of political unrest. In 1627, King Charles I imprisoned seventy-six gentlemen who refused to loan him money to fund wars against Spain and France. When five of them, known as the Five Knights, demanded release under habeas corpus, the King’s Bench sided with Charles, claiming that ‘reasons of state’ justified their detention. In response, Parliament passed the Petition of Right in 1628, asserting that no one could be imprisoned without cause—reaffirming the principle of habeas corpus. The episode provoked public backlash and was a prelude to broader constitutional conflict, which ultimately ignited a civil war and led to the execution of Charles I.

Between Charles I and Charles II, England abolished the monarchy, cut off a king’s head, experimented with republican rule, and eventually said “never mind” and brought the monarchy back. In 1660, King Charles II was restored to the throne, beginning the period known as the Restoration. Though he brought back the monarchy, he had to accept certain limitations and a more powerful Parliament.

Under King Charles II, England was rife with political instability, plots, and purges. He and his ministers were accused of ‘disappearing’ opponents without trial. Prompted by growing outrage, Parliament passed the Habeas Corpus Act of 1679 to curb royal abuse. This landmark law formalized procedures, imposed penalties on noncompliant officials, and extended the right to challenge unlawful detention to all subjects—not just nobles—making habeas corpus a statutory right for all.

Early American settlements brought habeas corpus’ influence across the Atlantic ocean. The American colonists deeply valued the writ as part of their rights as Englishmen. After independence, habeas corpus was enshrined in the U.S. Constitution (1789) in Article I, Section 9, stating:

“The Privilege of the Writ of Habeas Corpus shall not be suspended, unless when in Cases of Rebellion or Invasion the public Safety may require it.”

American courts have long recognized that the writ of habeas corpus is available to all individuals under U.S. jurisdiction, regardless of citizenship or social status. This principle has been consistently upheld in a series of landmark cases, from Ex parte Dorr (1845) to Rasul v. Bush (2004).

The Magna Carta planted the legal seed of due process, and habeas corpus grew from that seed as its practical enforcement mechanism. Enlightenment thinkers like John Locke and later William Blackstone emphasized natural rights and the universality of liberty, reinforcing the idea that habeas corpus applied to all persons, not just the privileged. Over the centuries, it evolved into a powerful tool for checking royal and executive abuse of power. For this very reason, habeas corpus has often been at the center of political turmoil. Born of rebellion, its history is as turbulent as any saga of power and resistance, marked by a long and bloody trail.

Today, habeas corpus resurfaces in legal battles over mass deportations, echoing its long-standing role as a check on executive overreach.

As habeas corpus repeatedly got in the way of deporting undocumented immigrants and arresting student dissenters, the Trump administration began advancing narratives about the potential suspension of the writ. Stephen Miller stated that the administration is “actively looking at” suspending habeas corpus to address illegal immigration, citing the Constitution: “The Constitution is clear — and that, of course, is the supreme law of the land — that the privilege of the writ of habeas corpus can be suspended in a time of invasion. So it’s an option we’re actively looking at.”

The administration’s consideration of suspending habeas corpus has spooked legal experts, who argue that such a move would challenge constitutional norms and the separation of powers. Steve Vladeck, a Constitutional Law Scholar and professor of law at the Georgetown University Law Center, emphasized that only Congress has the authority to suspend habeas corpus(PBS): “Habeas is so fundamental that it is a right in the original Constitution under Article I, and the overwhelming consensus is that only Congress can suspend habeas corpus.”

As the Constitution does not provide a method for suspending the writ of habeas corpus, what historical precedents exist for its suspension in the United States?

Suspension of Habeas Corpus in US history

In the history of the United States, habeas corpus has been suspended only a few times and always under extraordinary circumstances. The first of such events came in the 1861 during the civil war; President Abraham Lincoln unilaterally suspended the writ to allow the detention of suspected Confederate sympathizers and spies without immediate judicial oversight, setting off heated debate over whether the power to suspend it lies with the President or Congress.

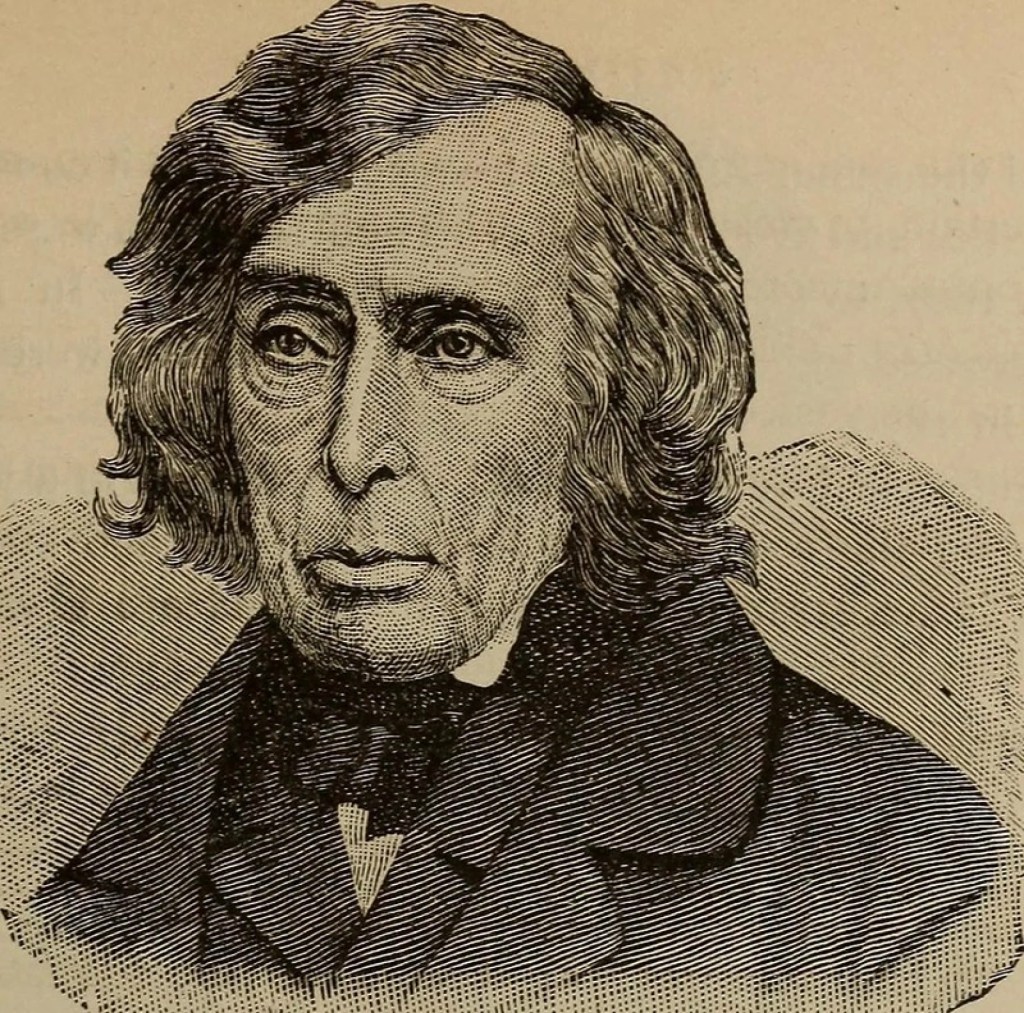

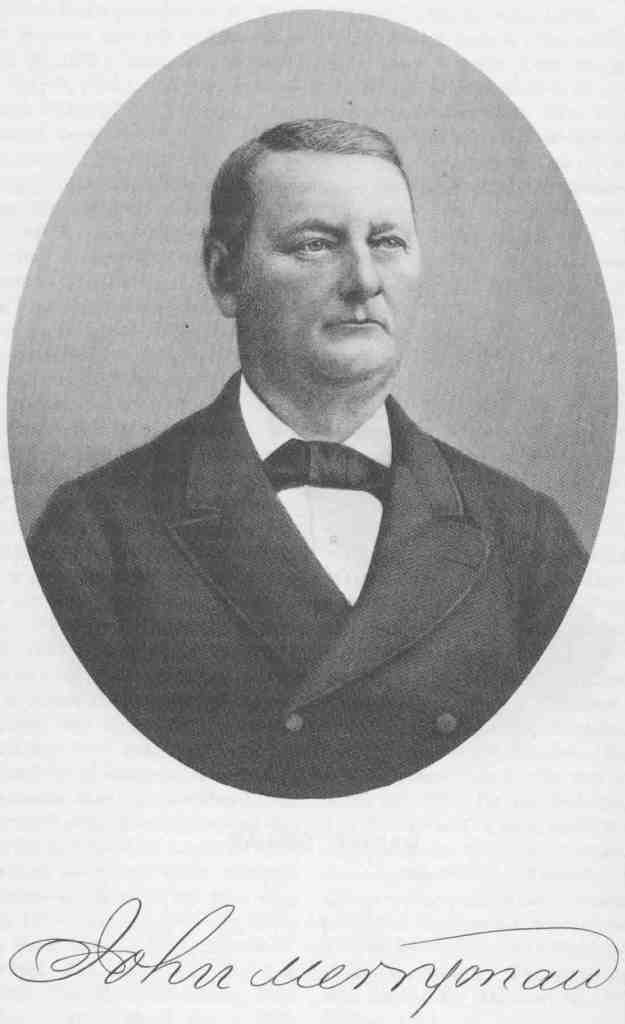

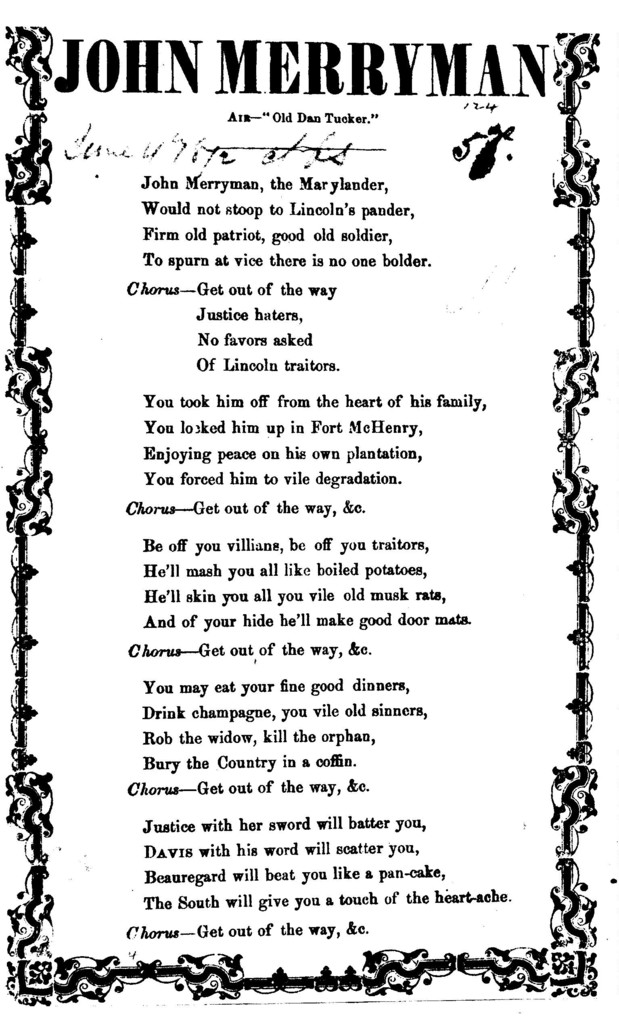

Chief Justice Roger B. Taney ruled, in the 1861 case of Ex parte Merryman, that only Congress could suspend habeas corpus, but Lincoln ignored the decision. Congress later addressed the issue by passing the Habeas Corpus Suspension Act of 1863, which authorized the President to suspend the writ when “the public safety may require it,” thereby retroactively legitimizing Lincoln’s earlier actions.

Credit: Internet Archive book image/LOC/Flickr/Creative Commmons

Suspension of habeas corpus happened again during the Reconstruction era, under President Ulysses S. Grant, as part of efforts to suppress Ku Klux Klan violence in South Carolina. The Enforcement Act of 1871, also known as the Ku Klux Klan Act, authorized Grant to suspend the writ and deploy federal troops to arrest and prosecute Klan members, aiming to restore law and order in the South.

During World War II, following the attack on Pearl Harbor, Hawaii Governor Joseph Poindexter declared martial law and suspended habeas corpus under the authority of the Hawaiian Organic Act. Although this suspension faced little controversy, it set the stage for the notorious internment of Japanese Americans, during which approximately 120,000 people of Japanese descent were forcibly relocated and incarcerated in ten camps under the pretext of national security. Since habeas corpus was never formally suspended on the mainland, the Supreme Court’s decision in Korematsu v. United States (1944), which upheld the internment policy, has been widely condemned as a grave constitutional error and a failure to protect civil liberties during wartime.

Although not a formal suspension, the Military Commissions Act of 2006 attempted to strip foreign detainees at Guantanamo Bay of their right to habeas corpus, effectively denying them access to challenge their detention in U.S. courts. This sparked one of the most significant constitutional showdowns of the post-9/11 era. In Boumediene v. Bush (2008), the U.S. Supreme Court struck down key parts of the Act. The Court decided that detainees at Guantanamo—yes, even those not on U.S. soil—still have the constitutional right to habeas corpus. After all, the U.S. may have outsourced detention, but it can’t outsource its legal obligations.

Extended Meaning of Habeas Corpus

While habeas corpus is most commonly associated with challenging unlawful imprisonment, its scope and use have expanded over time to cover a range of legal contexts where personal liberty is at stake.

Parents and guardians can use it to challenge custody disputes. Patients in psychiatric hospitals can file to question whether their confinement is lawful. Non-citizens, especially asylum seekers or those facing deportation, can use it to protest prolonged or unlawful detention by immigration authorities. Habeas corpus could also be a legal lifeline for those facing extradition, probation violations, or denial of bail—not necessarily a ticket to freedom, but at least a chance at a proper hearing.

There have even been legal attempts to file habeas corpus on behalf of animals, arguing they were unlawfully detained. Judges have mostly said, “Nice try”. But in 2015, the Nonhuman Rights Project (NhRP) pulled off a historic first: New York County Supreme Court agreed to hear a habeas corpus case for two chimpanzees, Hercules and Leo. NhRP followed it up in 2018 with another success–this time for Happy the elephant, who probably didn’t realize she was making legal history.

Habeas corpus has a nickname–the Great Writ, because it is deemed the most fundamental safeguard of individual freedom against arbitrary state action. It has become a cornerstone of modern democracy, crossing oceans and extending its reach globally. Many democracies worldwide have adopted habeas corpus or similar protections in their legal systems. International human rights frameworks, like the European Convention on Human Rights, also include similar protections. Throughout its long and turbulent history, habeas corpus has remained the legal fulcrum in the perpetual struggle between state power and individual liberty. It is less a settled doctrine than a living challenge—a tug of war between authority and human rights, revisited in every generation. For anyone confined behind bars, whether in a medieval dungeon or a modern detention center, the ancient plea resonates with urgency: that the court will declare, ‘You shall have the body.’

Leave a comment