Beneath the Waters, The Key to Predicting Earthquakes May Surface

With a recent string of small earthquakes hitting the LA region, close to my home, I found myself thinking about this geological phenomenon. Over 100,000 earthquakes are felt worldwide each year—was there anything I could do? Lucy Jones, a seismologist who spent three decades at the US Geological Survey, notes in a BBC article that “the human need to make a pattern in the face of danger is extremely strong.” Earthquakes are scary, and what makes them even scarier is that they’re unpredictable: we never know when the next “big one” will hit. Earthquakes and tsunamis have wreaked havoc on human civilization since the beginning of time, with the earliest recorded occurring in the 2000s BCE. And we’ve been trying to explain why they occur for nearly just as long.

Humans have tried to scientifically predict earthquakes since the 300s BCE, when Aristotle hypothesized that winds within the earth caused its surface to shake. In 132 CE, Chinese philosopher Zhang Heng invented the earliest known seismoscope, called Houfeng Didong Yi (“instrument for measuring the seasonal winds and the movements of the earth”). The seismoscope featured eight dragon heads arranged around an urn in the eight principal directions of the compass, with a toad sitting below each head. In the event of an earthquake, one or more dragons would drop a ball into the open mouth of their respective toad. The direction of the shaking could be determined by the position of the dragons that released their balls.

Modern seismology began to develop in earnest in the 1800s. Luigi Palmieri, an Italian physicist and meteorologist, created the first electromagnetic seismograph in the 1850s. His work laid the ground for English professors John Milne, James Ewing, and Thomas Gray to invent the first seismic instruments sensitive enough for scientific research. In the late 1800s and early 1900s, Grove Karl Gilbert and Harry Fielding Reid found that faults were a primary feature of earthquakes rather than a secondary result, and that earthquakes occurred due to a gradual accumulation of stress in the earth’s surface. Japanese researcher Fusakichi Omori, who studied the aftershock activity of large earthquakes, developed equations that scientists still use today. Seismological research skyrocketed in the late 20th century, bringing us to the early warning capabilities we know today.

Houfeng Didong Yi , as invented by Chinese seismologist Zhang Hen in 132 CE

To dive deeper into how earthquake science evolved in the late 1900s and early 2000s, Youth Journalism Alliance spoke to Jian Lin, senior scientist and marine geophysicist at the Woods Hole Oceanographic Institution. Dr. Lin’s research on earthquakes and tectonic plates has been essential for developments in understanding the relationship between earthquakes, tsunamis, and the ocean. Before one of his papers would go on to become most-cited of the decade in his field, however, Dr. Lin was just a high schooler trying to make a difference. After the devastating Tangshan earthquake of 1976, a magnitude 7.5 quake that killed over a quarter of a million people, Lin’s teacher formed a team of kids to be earthquake volunteers. They measured the water level of wells and the conductivity between trees using devices such as a voltmeter. By gathering results like these from various schools in the region, the local seismological bureau hoped to have a better chance at preparing for major earthquakes. “If all the schools reported a water level rise at the same time, they would know that something might have been happening,” Lin explained. “As an earthquake volunteer, we hoped that we could contribute to the science we called earthquake forecasting at that time. Obviously, while the forecasting method was scientific, it was still relatively immature.”

Since Lin’s high school years and even his early research days, technology has advanced significantly. “When I did my first expeditions at the sea, I was using radios, not even phones,” Lin said. “When you finished your sentence, you said, ‘Roger over.’ Things are very different today. Now, on the ship, we can have internet service almost in real time…we can send the data back right away at the sea.”

In addition to high-speed internet access, technology such as autonomous underwater vehicles and precise satellite motion detection have improved the accuracy of earthquake research. However, according to USGS, scientists are still unable to accurately predict earthquakes—all we can do is detect them as soon as they occur and immediately warn people in the vicinity. “Earthquake waves travel at four kilometers per second,” Lin explained. “So if you are 40 km away from the center of the earthquake, you will have about 10 seconds.”

It might not seem like much, but those seconds save lives. They may give someone just enough time to prepare for an earthquake’s impact. Current earthquake early warning systems activate almost immediately due to state-of-the-art sensors monitoring the ocean. In the future, however, scientists hope to have more than just ten seconds. Dr. Lin believes that advances in seismometer and satellite technology can provide huge amounts of data that may be used to train AI models. Indeed, machine learning seems to be the next hope for earthquake forecasting: AI software can detect earthquakes faster and predict them more accurately. According to National Geographic, “AI multiplies and accelerates the capabilities of a single scientist. It can process many seismic records simultaneously, rendering them with great precision and in three dimensions faster than any human could in the same amount of time.”

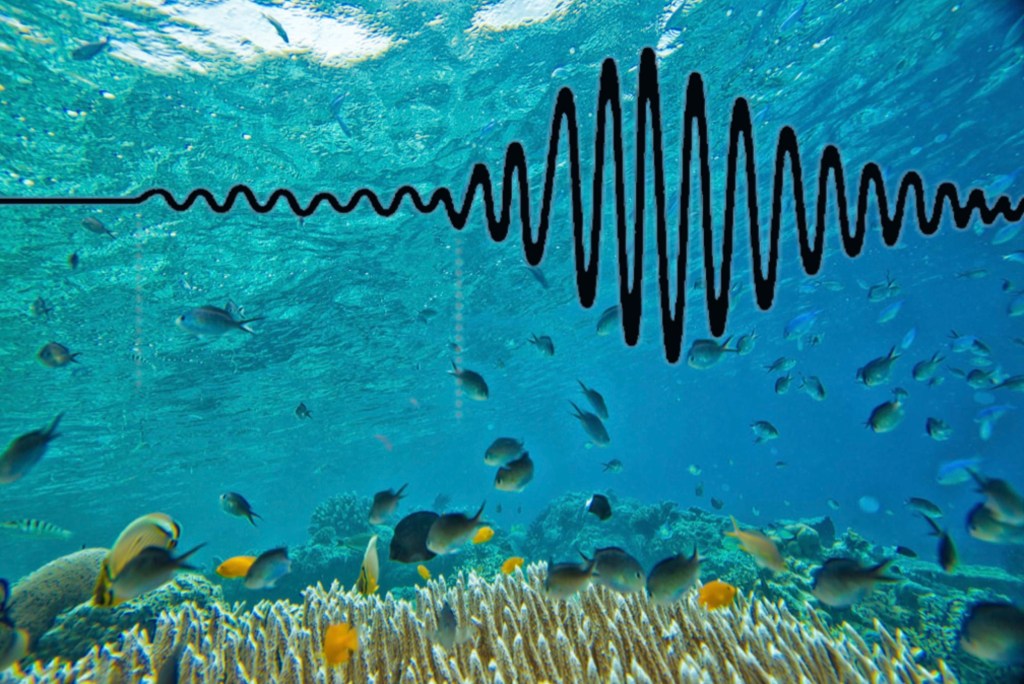

Beyond AI, other methods have also advanced in the field. For example, fiber-optic cables may be used to improve detection. The expansive underwater cable system, which runs along the ocean floor, can detect tremors and potentially improve early warnings. Distributed Acoustic Sensing (DAS) technology allows cable networks to continuously monitor seismic activity and increases the density of information. Additionally, networks such as the ShakeAlert system have integrated satellite and GPS data, allowing quakes to be detected and warnings to be sent out faster.

However, these approaches currently fall short of earthquake prediction. Dr. Lin thinks that one underexplored key to earthquake forecasting lies underwater: “Very few people in our society, among all ages, understand the importance of the ocean.” Even though we have fiber-optic cable and satellite data, we aren’t utilizing it enough. The ocean can tell us more than just tremors; it can reveal the story of earthquakes beneath the surface through tectonic plate movements. Additionally, the most powerful earthquakes and tsunamis occur in subduction zones, where one plate is thrust under another deep below the oceanic crust. After joining the Woods Hole Oceanographic Institution, Dr. Lin studied, among other things, mid-ocean ridges: “We revealed that the Mid-Atlantic Ridge, which is very long—all the way from the North Pole to the mid-Atlantic, then all the way to the South Pole—looks like a very long, continuous line. In fact, it is broken up into segments, like the bones in our spines.” The individual segments of the ridge, between 20 to 80 kilometers long, provided insights into how tectonic plates and hydrothermal vents in that area formed.

Ocean research is critical to understanding why earthquakes and tsunamis occur. Yet 95% of the ocean remains unexplored, even though it covers around 70% of our “blue planet.” In fact, it’s commonly said that we know more about deep space than our own oceans. “It becomes easier to learn about space because we can send many satellites to space, but it’s harder to do the same with the ocean,” noted Lin. After all, Mount Everest can fit easily inside the Mariana Trench—the ocean’s depth certainly remains a challenge for scientists. However, understanding marine geophysics and the movement of tectonic plates beneath the seas is critical for improving earthquake research. In addition to further scientific exploration, Dr. Lin believes that getting the public to care about the ocean is critical: “If people do not understand the problems when we make big decisions, they do not know why we should support, for example, protecting the oceans, or reducing pollution in the oceans.” By increasing ocean literacy, Dr. Lin hopes to do justice to the story of the seas. “It doesn’t matter what age you are, you are already connected to the ocean, like it or not.”

Graph by Frank Spada

Humans have attempted to predict earthquakes for over two millennia. From an ancient Chinese seismoscope to sophisticated AI models, we have yet to fully decipher the puzzle of when and why earthquakes occur. But hope may lie beneath the seas. As new technology and new methodology arises, scientists are getting ever closer to Dr. Lin’s ultimate goal: “My passion has always been that one day, we will be able to forecast earthquakes…that would be a major achievement for humankind.”

Leave a comment