Editor’s Pick

Science Fairs: the Barometer of American STEM Culture

Recently, heated debates have sparked in the Republican Party over the H-1B visa program and whether it ultimately benefits America. Tech entrepreneurs Vivek Ramaswamy and Elon Musk have argued that the program is necessary because American culture does not value intelligence enough, with Ramaswamy tweeting that “American culture has venerated mediocrity over excellence.” But are they perpetuating the tired trope of the bullied nerd, or does America truly favor its prom queens over its math champions?

Ramaswamy called for “our Sputnik moment” in his tweet, referencing the Space Race that propelled the popularization of science culture in America. He, Musk, and others believe that we have since lost that culture. Yet one relic of that time still thrums with life: the science fair. Has it, too, finally been overshadowed by social media and popularity contests? Or does it still offer hope for the scientists of the next generation? A cradle for young STEM talent, the science fair’s rise and fall over the years mirrors that of American academic culture. To truly understand how science is interwoven into the American story, we must travel all the way back to the 19th century.

The History of Science Fairs

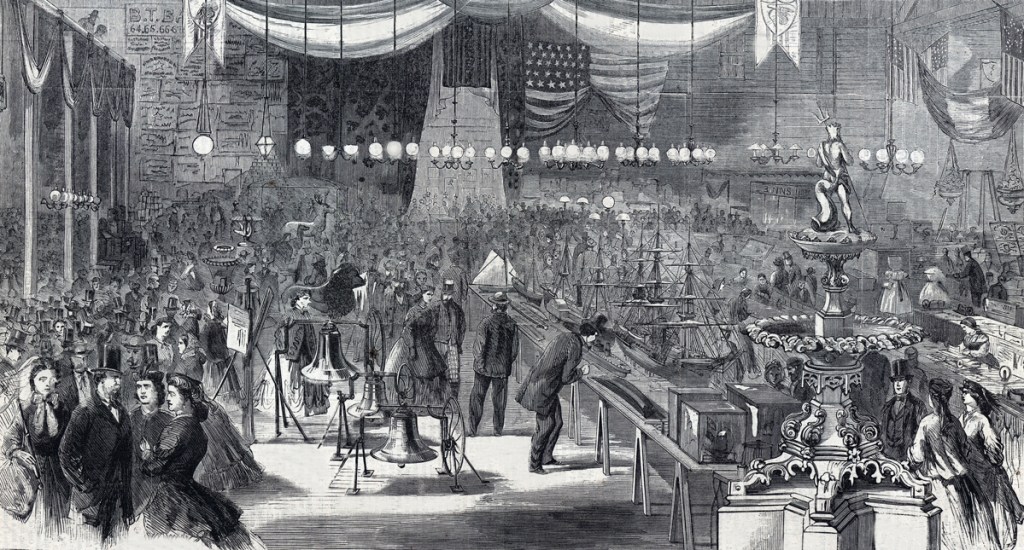

The thirty-sixth annual fair of the American Institute opens in New York City

It’s no coincidence that science and engineering fairs emerged in the U.S. in the late 20th century, evolving into a powerful movement that swept across the nation and later the globe. The seeds were sown for this development at the dawn of the industrial revolution.

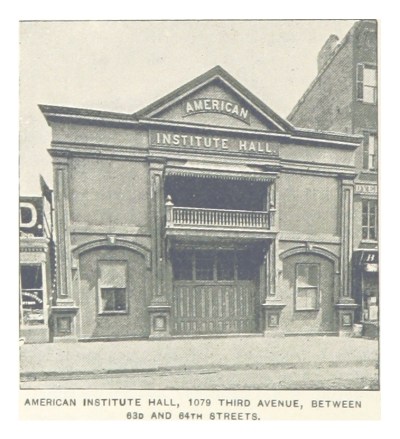

The very first “science” fair was technically an industrial exhibition held by the American Institute of the City of New York in 1828. Nearly 20,000 visitors came to see inventors showcase advancements in agriculture and manufacturing. Throughout the 19th century, the general public flocked to these fairs to have the first peek at innovations such as the Morse telegraph, Bell telephone, and Remington typewriter.

By the turn of the twentieth century, however, public enthusiasm for science exhibitions began to fizzle out—perhaps people had finally seen enough oversized telescopes. In response, the American Institute reinvented itself, shifting the focus of fairs toward children’s studies in nature and agriculture. Meanwhile, the American Museum of Natural History encouraged young minds to get up close and personal with the natural world, and major toy manufacturers like the A.C. Gilbert Company flooded homes with scientific toys, ensuring that many a living room became a makeshift chemistry lab. With these forces at play, the stage for the modern science fair was set. In 1928, the American Institute opened its first Children’s Fair to a crowd of approximately 35,000 spectators. However, the fair came to an end in 1941 due to financial difficulties faced by the American Institute.

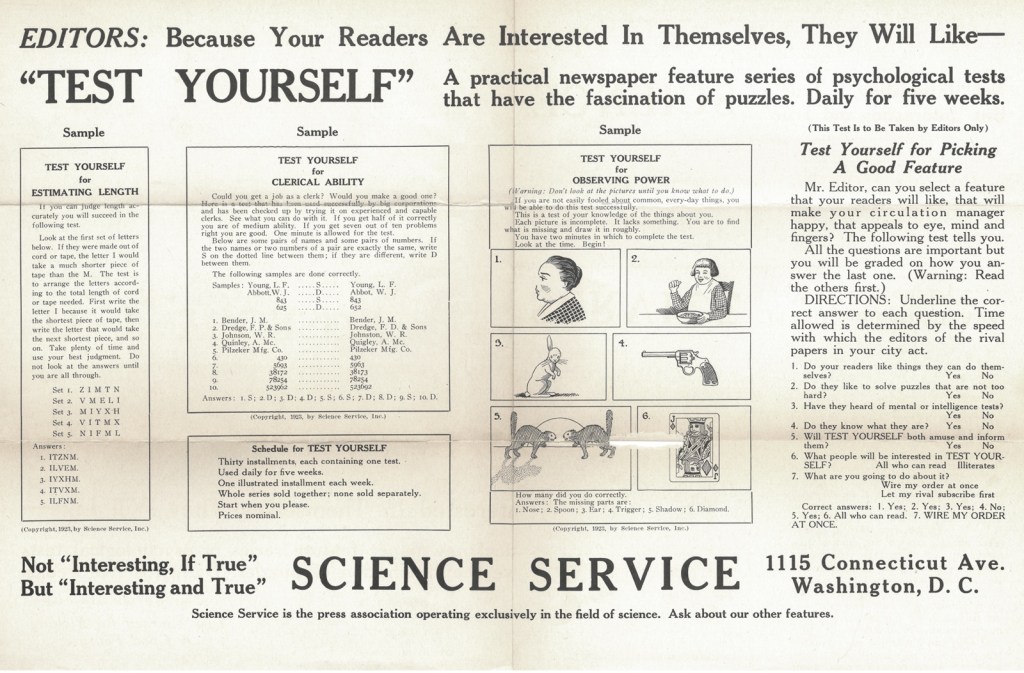

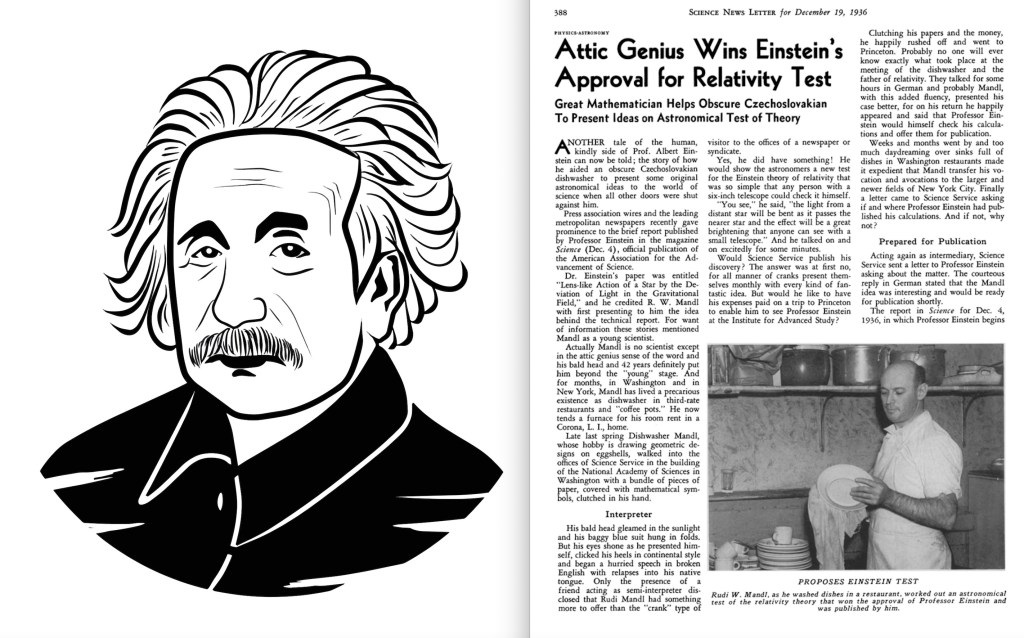

As the American Institute stepped back from its starring role in championing science education, other organizations eagerly grabbed the baton. Take the Science Service: founded in 1921 by newspaper magnate E.W. Scripps and UC professor William Ritter, its initial goal was to bridge the gap between esoteric scientists and the average citizen. The Science Service launched news and radio programs covering major scientific breakthroughs, including the life-saving discovery of penicillin, the slightly more explosive creation of the atomic bomb, and the Space Race, which was basically the Olympics but with rockets. Not content with just talking about science, the organization actively engaged the public, sent science kits to children, and even facilitated the first meeting between “amateur scientist” Rudi Mandl and Albert Einstein. The two hit it off so well that Einstein later published a paper on gravitational lensing based on Mandl’s work.

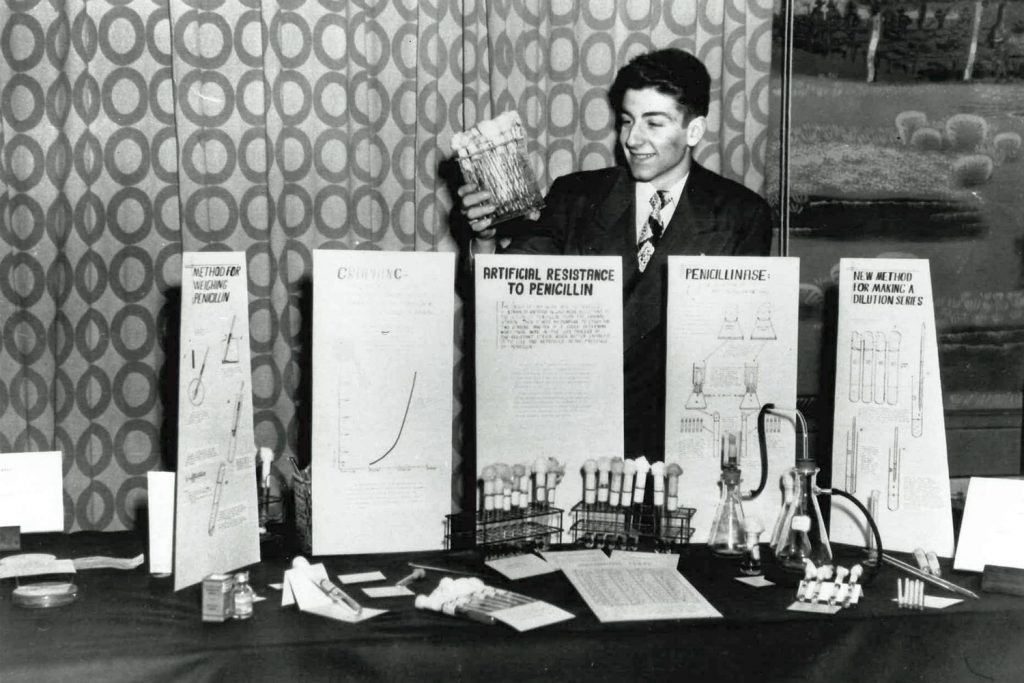

World War II didn’t just reshape nations—it supercharged science. With the realization that brainpower was just as critical as firepower, America set its sights on cultivating the next generation of STEM wizards. The hope? That a kid building a baking soda volcano today might be designing rockets tomorrow. Believing that science fairs could serve as talent scouts for future Einsteins and Teslas, the Science Service teamed up with Westinghouse Electric to launch the Science Talent Search (STS) in 1942, and doubled down with the establishment of National Science Fair (NSF) in 1950.

The launch of STS signaled the shift from educating citizenry to adopting a meritocratic approach. Original children’s fairs leaned heavily on nature exploration and informative exhibits: a top project showcased a diorama on the life cycle of a dogwood tree. Since the inception of STS, Science fairs were no longer just about knowing science—they were about doing science, complete with hypotheses, experiments, and enough data charts to make your head spin. With analytical skills as the top criterion, STS and NSF set out to find the ‘best and brightest’—and it worked. The proof? Four STS finalists from the competition’s first decade—Ben Mottelson, Leon Cooper, Sheldon Glashow, and Walter Gilbert—went on to snag Nobel Prizes. Not bad for a bunch of kids who probably started with baking soda volcanoes.

Following the success of STS, the number of science clubs multiplied after WWII. In 1941, there were about 700 clubs; by 1949, that number had skyrocketed to 13,000—because nothing says ‘join a science club’ like a Cold War arms race and the looming threat of Soviet superiority.

Then came 1957, aka the year America collectively panicked. The Soviet launch of Sputnik sent the nation into overdrive, determined to churn out young scientists faster than you could say ‘orbital trajectory.’ Government agencies jumped in, offering programmatic support and financial incentives to science fair participants, and the numbers reflected the frenzy: in 1957, about 250,000 students participated in science fairs; by 1962, that number had quadrupled to a staggering one million.

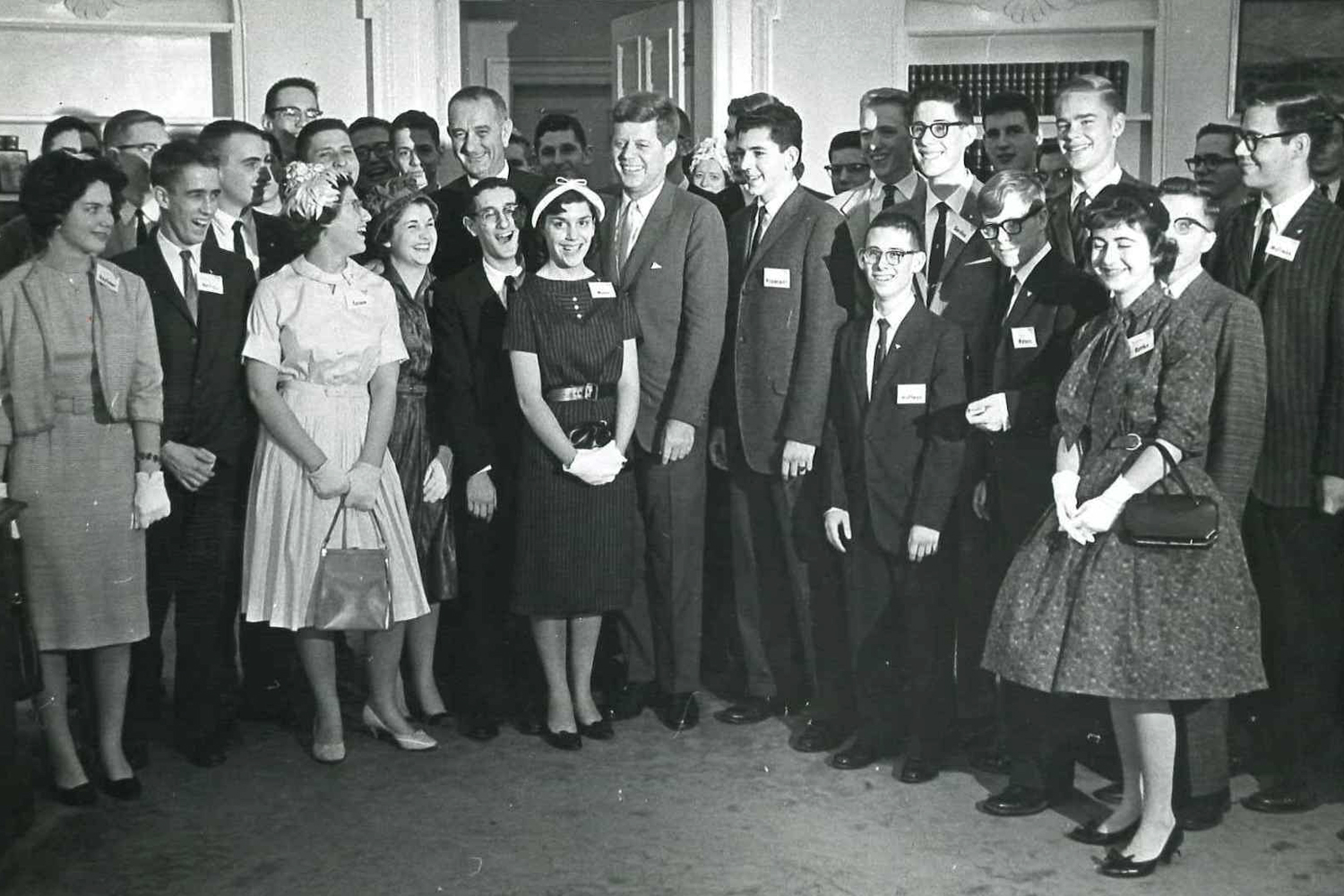

One shining example of America’s commitment to scientific excellence? The long-standing tradition of U.S. presidents personally meeting STS finalists—because nothing boosts your research credibility like a handshake from the leader of the free world. From Truman to Obama, nearly every president has honored these young scientists, proving that while political parties may disagree on almost everything, everyone can get behind really smart kids doing really cool science.

In 1958, NSF moved from the national to the international: it soon evolved into the International Science and Engineering Fair (ISEF) we know today. Now, ISEF draws over 175,000 high school students from across the U.S. and 80 other regions around the world.

As the popularity of fairs grew, the Science Service expanded its program to middle schoolers. In 1999, it collaborated with Discovery Communications to launch the Discovery Young Scientist Challenge, which later became Broadcom MASTERS and is now known today as the Thermo Fisher Scientific Junior Innovators Challenge. From middle school to high school, every chemistry-loving, rocket-building, slightly sleep-deprived teenager now has a stage to shine.

Maya Ajmera, President and CEO of Society for Science

Photo Credit: Society for Science

The Science Service, the powerhouse behind the largest national science competitions for middle and high schoolers, changed its name to Society for Science & the Public in 2008. In 2020, the organization rebranded again, simplifying its name to Society for Science. With its deep roots in science journalism, Society for Science keeps its finger on the pulse of the science community while expanding its reach by publishing science news and offering grants to teachers and nonprofits. Maya Ajmera, the President and CEO of Society for Science, has a bold vision: “every young person in this country can become a scientist or engineer if that’s what they want to be when they grow up.”

What Science Fairs Represent

When I interviewed Maya Ajmera, I asked her how the landscape of science fairs has changed. She noted that, despite the tools we use for research getting a pretty nice upgrade, the core of science fairs remains the same—science fairs are first and foremost about originality and scientific methodology.

Photo Credit: Kyle Ryan Kyle Ryan

The shape and form of the science fair, however, has gone through a complete metamorphosis over the years. According to Agnes Kelly of the American Museum of Natural History, back in 1928, the main criteria for judging in the original children’s fair was aesthetics—that diorama of a dogwood tree must have been quite a charmer! At that time, science fairs were more about the exhibition of science than actually digging into the research. Today, though, students are expected to do more than just make things look pretty – they are asked to approach their projects as real-world problems in need of solutions. To “begin with a problem,” a popular piece of advice from science fairs these days, requires students to inquire about knowledge independently beyond textbooks and classrooms. To find a solution, however, relies on collaboration with teachers, schools, mentors, fair organizers, and institutions that assist in the project. When a project is independently completed, it gives students a sense of scientific authority and enables them to find their role in science.

In 2019, girls swept all five of the top Broadcom MASTERS awards.

Photo Credit: Society for Science

Science fairs, however, have historically not been for everyone—participation has faced disparities in gender, race, region, and income. During the first decade of the Science Talent Search, there was only one African American finalist and only two in the first two decades of the competition. There were only three African American students who participated in the 1955 National Science Fair. Some of these numbers have increased: in 1972, not only did a female student clinch first place in the Science Talent Search, but five of the top ten winners were young women. While only 20% of science fair projects were submitted by female students in the 1930s, 48% of 2024 ISEF finalists were women. Frederick Grinnell, Professor in UT Southwestern Medical Center, published a study in 2022 that indicated significant ethnic diversity in the overall participation in high school science fairs. Of the students surveyed, the approximate distribution was Asian-32%; Black-11%; Hispanic-20%; White-33%; and Other-3%. Although an imbalance nonetheless persists, diversity has improved overall since the 1900s.

Unfortunately, regional overrepresentation remains a problem. In the first six years of STS, 18 states didn’t even have a single finalist while New York had a whopping 254 finalists and 235 honorable mentions. Has this imbalance improved since? Not quite. Today, science fairs are still dominated by states like California, Pennsylvania and Florida. Meanwhile, there are still many STEM deserts where participation remains low. In fact, Grinnell’s 2023 study found that 74% of students participating in Science and Engineering Fairs (SEFs) came from suburban schools, while fewer than 4% of SEF participants were from rural schools, even though national data shows that more than 20% of high school students attend rural schools.

A Fair Question: Is the Competition a Climate or a Curse?

While science fair culture consumed America in the 20th century, a New York Times article from 2011 observed that participation in science fairs had been declining since the turn of the century, reporting that “the Los Angeles fair, though still one of the nation’s largest, now has 185 schools participating, down from 244 a decade ago.”

The decline in participation has been partly blamed on stringent education policies that stretch schools thin, leaving teachers without the time or resources to adequately support students for science fairs. As a result, some districts simply did not have enough participating high schools to sustain their fairs. The issue is particularly pronounced in what Ajmera calls “STEM deserts.”

Criticisms have also arisen that modern science fairs have lost sight of learning and are mired in competition instead. The high stakes of science fairs have fueled fierce, intensive battles, turning these events into arenas of intellectual gladiatorship where only the sharpest minds survive. Some argue that it all boils down to a contest of parental privilege, with access to labs being the ultimate secret weapon, which in turn aggravates the problem of exclusion of underprivileged communities from the science fairs. “Are science fairs fair?” questioned Siddhu Pachipala, a multiple-time ISEF finalist who had participated in science fairs every year since middle school. Pachipala wrote in a Slate article that “before you even walk in to set up your board, the cards are already stacked for or against you. If your mom works at the local university and lets you piggyback off her Alzheimer’s research, you have a leg up. If you can spend thousands of dollars to get professional interview coaching, you have a leg up. If your school has state-of-the-art clean rooms, 3D printers, or virtual-reality headsets, you have a leg up.” A PLOS One research paper reports that students who receive help from scientists and coaches are more likely to win fairs and retain an interest in a STEM career.

Research suggests that individuals driven primarily by competition are more likely to quit than those motivated by a genuine love of learning. Yet, in the current high-pressure academic climate, many students view science fairs as a resume-booster rather than a learning opportunity. Eager to impress the judges, some may sensationalize their results, despite the reality that science research is often slow, tedious, and full of dead ends. There are also growing concerns that the original purpose of science fairs might be lost in the rush to craft the next splashy “young genius” story. In today’s society, with the pressure for college admission at an all-time high, will students prioritize meaningful research, or will the pursuit of awards take center stage? Educators worry that the emphasis on competition may drain the joy out of science, and eventually steer science fairs away from their original intent. Grinnell surveyed 302 students in 2017 from high school through graduate school about their experience with science fairs. As part of his analysis, he discovered that while the students generally enjoyed participating in science fairs, they disliked the competitive aspect.

Tina Jin (top) and Samvith Mahadevan (bottom), 2024,

Thermo Fisher Junior Innovators Challenge Finals Week.

Photo Credit: Society for Science

However, participants of the Thermo Fisher Scientific Junior Innovators Challenge, the largest science fair for middle schoolers nationwide, see things differently. Samvith Mahadevan, the winner of the $10,000 Lemelson Foundation Award for Invention, does not mind being measured against his peers, noting that “even if you don’t win, you can still learn from other people’s projects.” Tina Jin, who took home the top prize of the competition, adds that the experience “wasn’t as competitive as I thought it would be…when you’re immersed in the challenges, you don’t really realize you’re being judged.” At the higher levels of these competitions, students genuinely enjoy the work that they are doing and see the fairs as an opportunity to grow. As a former alumna of 1985 STS, Ajmera herself believes that “competition is a part of our…blood in this country, and I wouldn’t take that away.”

Although competition can certainly seem daunting, suppressing it could stifle STEM talent from reaching their full potential, and tipping science fairs towards an “Harrison Bergeron”-esque dystopia, where everyone’s science projects are equally… average. On the flip side, competition can be a powerful motivator against complacency, and learning how to handle wins or losses is an important life skill. According to Ajmera, science fairs promote “original thoughts.” Judges typically focus on evaluating the scientific process behind student projects, rather than just the final product or outcome. An overlooked benefit of science fair competition is that learning does not have to end at the conclusion of the project. The project presentations, judge interviews, and peer discussions likely spark deeper reflection on the principles of scientific inquiry, inspiring students to think critically about their work and the science behind it. An experiment yielding negative results should be celebrated as a success. Science fairs are a rare stage where losing is as glorious as winning. In Ajmera’s eyes, the science fair offers a unique blend of learning and character building that embodies what science research truly means.

A Bright Future for Science

Aritro speak at the Youth Parliament of the UN General Assembly

Photo Credit: Non-Trivial

As the times march on, so do modern science fairs. Many new programs are adopting clever strategies to reel in student participation. Take online programs like NonTrivial, for example. Unlike your standard science fair, NonTrivial guides students step-by-step through developing a viable research proposal over several months. It’s like having a personal science coach, except without the whistle. At the end of it all, winners get actual monetary grants to take their ideas to the next level. These initiatives are igniting a fresh fire for STEM learning.

This renewed passion is not just confined to the scientific community. With the rise of AI, robotics, quantum computing, and autonomous driving, the general public has suddenly become obsessed with the possibilities. These breakthroughs have kickstarted a fresh wave of scientific curiosity, especially among younger generations. The rapid development of these cutting-edge technologies is motivating young minds to explore and contribute to fields previously deemed distant or impossible to navigate. As the barometer of STEM culture, science fairs have clearly sensed the pulse of this movement, with many projects now diving headfirst into these fields.

Through it all, no matter in what form, science fairs ultimately tie back to their roots. Even though we use different tools to do research today, Ajmera notes that “it’s still about inquiry.” At its heart, science research is about asking questions: How can I solve this problem? How can I change the world? A desire to use STEM to solve real-world issues still remains at the center of the science fair.

When asked to describe science fairs in one word, Ajmera didn’t hesitate: “Innovation.” America pioneered the modern science fair, and the passion for advancements in science is woven into our DNA.

The fuel for the Sputnik moment was, and always will be, the undying spirit of innovation: the next launch is on the horizon, and a new generation stands ready.

Leave a comment